Enabling cuddles with delivery room CPAP

This transition is navigated without complication in most cases, with 85% of babies beginning to breathe without intervention immediately following birth [1]. However, premature birth may present problems during this transition as a result of baby’s lungs still developing. Babies born early often need respiratory support to aid with their transition and common practice has often involved the use of positive pressure ventilation (PPV).

More recently, evidence suggests the use of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) in the delivery suite, with the term ‘Delivery Room CPAP (DR CPAP)’ developed as the application of positive pressure to stabilise a baby in respiratory distress at or following birth. This blog will explore the topic.

The preterm baby needing support

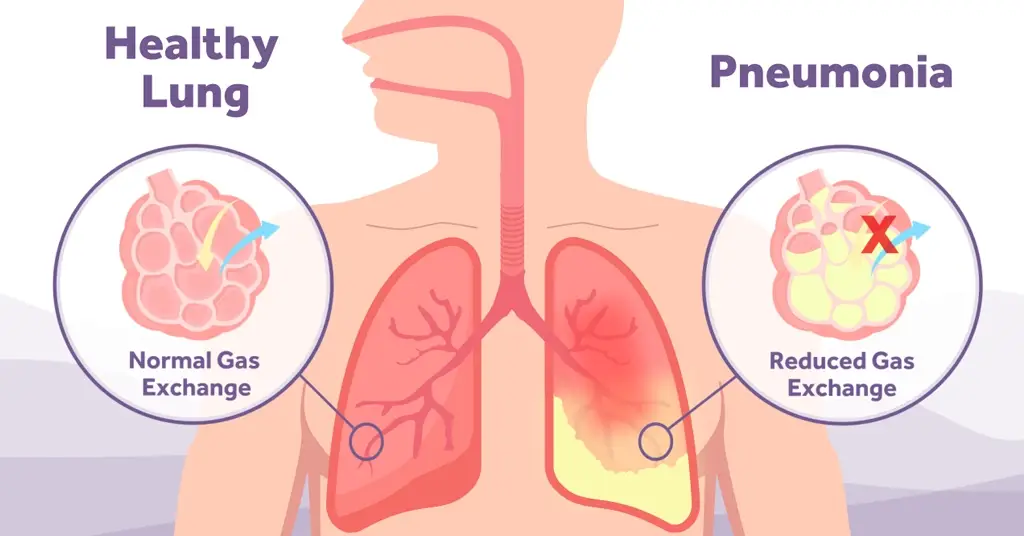

The additional complexities in achieving an ‘intervention free’ transition in preemies is caused by lack of developed alveoli, reduced lung volume, limited surface area and a lack of smooth muscle in the lungs [2]. These complexities mean that respiratory support is often required to ensure smooth transition and successful stabilisation as gas exchange is inhibited, there is reduced surfactant production and preterm babies have trouble in establishing functional residual capacity (FRC).

The complications also make the lungs fragile, and it is suggested that the respiratory support provided for a baby immediately following birth should be gently delivered to preterm infants, compared to term infants, to avoid injury caused by excessive mechanical stress [3]. It is essential therefore, that these babies are supported as early as possible following birth, with the most appropriate intervention available.

The support for CPAP

American paediatrician, Dr Mary Ellen Avery, has been credited with much of the pioneering research efforts into the causes of infant respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) through the identification of pulmonary surfactant.

As early as 1987, she was suggesting the use of CPAP, over traditional mechanical ventilation, to reduce lung injury in preterm infants through avoiding barotrauma and volutrauma [4]. The respiratory complications, already discussed, cause these preterm infants to have a high risk of acute lung injury which increases the chances of developing chronic lung disease, in particular, Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia (BPD).

It is estimated that around 38.8% of very preterm infants develop BPD at some level [5], which can lead to long term effects such as impaired lung function which can continue into childhood and in some cases, cause lifelong complications.

With one of the largest postnatal risk factors for BPD being the use of mechanical ventilation [6] it corresponds to trial results which have shown that trying to prevent intubation in the delivery room leads to less severe lung injury and that early use of CPAP reduces BPD [7]. The use of CPAP immediately after baby is delivered is essential for alveolar recruitment and forming the functional residual capacity in preterm babies. This should lead to a reduction of infants requiring mechanical ventilation [8].

The delivery room management of preterm babies has become more evidence based, with trials such as ‘COIN’, ‘SUPPORT’ and the DR Management study [9,10,11] helping shape and drive forward best practice in terms of delivery room CPAP. Global and European consensus guidelines now make recommendations on the use of CPAP for delivery room stabilisation. The European Consensus Guidelines on the management of Respiratory Distress Syndrome recommend that spontaneously breathing preterm infants should receive CPAP support during delivery room stabilisation to reduce lung injury and BPD [12].

Maintaining the respiratory stability of baby using CPAP in the delivery suite can also provide other potential benefits, namely the provision of better and longer delivery room cuddles and the use of Less Invasive Surfactant Administration (LISA) [12]. The benefits of skin-to-skin care or kangaroo cuddles is discussed in this blog with the earliest preterm babies benefiting the most from delivery room cuddles [13].

Is there something we can learn from Kangaroos?

Recent studies show the early introduction of Kangaroo care can have a dramatic positive impact on the outcomes for preterm and low birth weight babies.

A stable CPAP interface gives the caregiver peace of mind that baby is being supported while the all-important cuddle takes place, meaning cuddles may be delivered over a longer time increasing the benefits to mum and baby. The use of a CPAP system instead of mechanical ventilation also allows for the delivery of early surfactant that may otherwise be delayed until ward admission or have to be delivered using a more invasive method [12,14]. The combined use of early CPAP and early LISA has been shown to result in less need for mechanical ventilation, reduction in BPD [15] and a reduction in Intraventricular Haemorrhage (IVH) [16].

The use of early CPAP may be easily introduced to a perinatal environment through good perinatal teamwork to ensure the best care pathway for each baby is delivered. Various methods of delivering CPAP in the labour ward exist and exploration of the best solution to implement CPAP, delivery room cuddles and early LISA in this environment should provide the optimal outcome for baby, parents and caregiver.

[1] Madar, John, et al. “European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: Newborn resuscitation and support of transition of infants at birth.” Resuscitation 161 (2021): 291-326.

[2] Gleason, Christine A., and Sandra E. Juul. Avery’s diseases of the newborn e-book. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2017.

[3] Martherus, Tessa, et al. “Supporting breathing of preterm infants at birth: a narrative review.” Archives of Disease in Childhood-Fetal and Neonatal Edition 104.1 (2019): F102-F107.

[4] Avery, Mary Ellen, et al. “Is chronic lung disease in low birth weight infants preventable? A survey of eight centers.” Pediatrics 79.1 (1987): 26-30.

[5] Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, National Neonatal Audit Programme Annual Report on 2021 data: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/national-neonatal-audit-programme-summary-report-2021-data [website accessed 25 April 2023]

[6] Thekkeveedu, Renjithkumar Kalikkot, Milenka Cuevas Guaman, and Binoy Shivanna. “Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a review of pathogenesis and pathophysiology.” Respiratory medicine 132 (2017): 170-177.

[7] Subramaniam, Prema, Jacqueline J. Ho, and Peter G. Davis. “Prophylactic or very early initiation of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for preterm infants.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 10 (2021).

[8] Foglia, Elizabeth E., Erik A. Jensen, and Haresh Kirpalani. “Delivery room interventions to prevent bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely preterm infants.” Journal of Perinatology 37.11 (2017): 1171-1179.

[9] Morley, Colin J., et al. “Nasal CPAP or intubation at birth for very preterm infants.” New England Journal of Medicine 358.7 (2008): 700-708.

[10] SUPPORT Study Group of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Neonatal Research Network. “Early CPAP versus surfactant in extremely preterm infants.” New England Journal of Medicine 362.21 (2010): 1970-1979.

[11] Dunn, Michael S., et al. “Randomized trial comparing 3 approaches to the initial respiratory management of preterm neonates.” Pediatrics 128.5 (2011)

[12] Sweet, David G et al. “European Consensus Guidelines on the Management of Respiratory Distress Syndrome: 2022 Update.” Neonatology vol. 120,1 (2023): 3-23.

[13] Linnér, Agnes, et al. “Immediate skin‐to‐skin contact may have beneficial effects on the cardiorespiratory stabilisation in very preterm infants.” Acta Paediatrica 111.8 (2022): 1507-1514.

[14] Herting, Egbert, Christoph Härtel, and Wolfgang Göpel. “Less invasive surfactant administration: best practices and unanswered questions.” Current opinion in pediatrics 32.2 (2020): 228.

[15] Dargaville, Peter A., et al. “Effect of minimally invasive surfactant therapy vs sham treatment on death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants with respiratory distress syndrome: the OPTIMIST-A randomized clinical trial.” Jama 326.24 (2021): 2478-2487.

[16] Abdel-Latif, Mohamed E., et al. “Surfactant therapy via thin catheter in preterm infants with or at risk of respiratory distress syndrome.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 5 (2021).