Breath of Life: Navigating Oxygen Therapy for PARDS

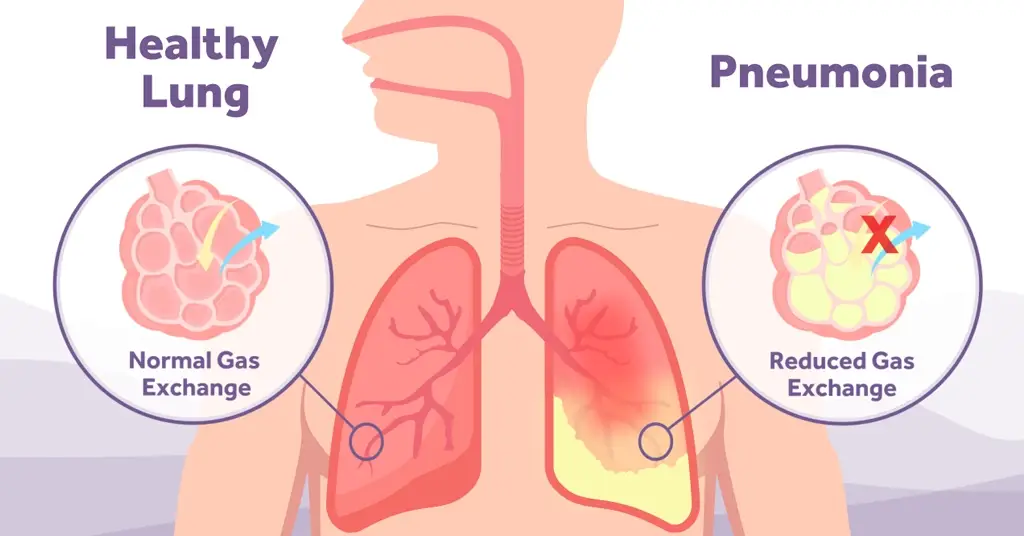

Paediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (PARDS) is a type of acute lung injury that occurs in critically ill children. It is a severe and life-threatening condition that develops rapidly and causes difficulty in breathing, reduced oxygen levels in the blood and organ failure. It is similar to the adult counterpart but has slightly different definitions. The Paediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference Group (PALICC) set out in 2015 to develop paediatric specific definitions for acute respiratory distress syndrome alongside recommendations for treatment and future research priorities, these guidelines were updated in February 2023 involving panellists from 15 different countries (1).

Recently, there has been a wealth of new knowledge regarding (P)ARDS, with emerging concepts in the pathobiology, lung protection (driving pressure, mechanical power, patient self-inflicted lung injury), and use of new technologies such as High Flow Oxygen Therapy (HFOT). In the updated PALICC-2 a revised definition and key concepts for treatment related to stratifying PARDS severity at least four hours after initial PARDS diagnosis for both invasive and non-invasive ventilation (NIV), allowing for the diagnosis of ‘possible PARDS’ for children on nasal modes of support such as HFOT (2).

Traditionally, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in children is diagnosed using the American-European Consensus Conference (AECC) criteria. The global standard definition is the 2012 Berlin definition – this has been adapted for use in paediatric practice.

PALIC guidelines states that ARDS occurs within seven days of the known insult and can be graded in severity using the Oxygenation index (Mild 4-8, Moderate 8-16 and Severe >16) or Oxygen Saturation Index (OSI). For a PARDS diagnosis, which cannot be otherwise explained by cyanotic heart disease, chronic lung disease and/or left ventricular dysfunction.

The PALICC-2 guidelines state that all patients less than 18 years old without active perinatal lung disease should be diagnosed with PARDS using PALICC-2 criteria, furthermore, practitioners can use either the PALICC-2 or neonatal definition (Montreux NARDS) for neonates and can use either the PALICC-2 or adult definition (Berlin ARDS) for young adults (1,2).

Children with ARDS vary in terms of age and lung development and is most often caused by pneumonia, sepsis, and aspiration. It can also occur as a complication of other medical conditions such as cancer, trauma, burns, pancreatitis, inhalational injury, transfusion, cardiopulmonary bypass, congenital heart disease, and autoimmune disorders. ARDS is associated with significant morbidity related to secondary infection, prolonged hospital admission, critical illness neuropathy and a reduction in health-related quality of life. The mortality associated with ARDS is high in children (10-12% in mild to moderate ARDS and 33% in severe cases (3). Studies on paediatric ARDS report an incidence of approximately 1% to 4% of all paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) admissions (4-6).

Treatment of PARDS typically begins with treatment of the underlying disease process, PALLIC guidelines also outline specific mechanical ventilation strategies such as target tidal volumes 5-8mL/kg of IBW or 3-6mL/kg, gas exchange goals, sedation, neuromuscular blockage, inhaled nitric oxide, proning, steroids, high frequency oscillatory ventilation and ECMO are also discussed in these guidelines. Non-respiratory supportive care is also discussed and covers treatment such as fluid management, nutrition, blood transfusion, sleep and rehabilitation.

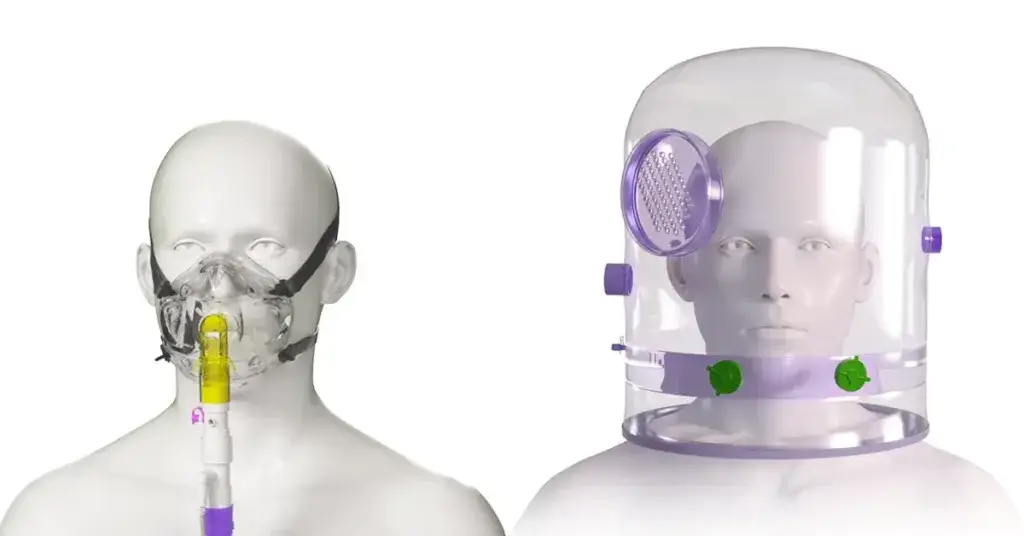

It is important to note that NIV is a widely used treatment of respiratory failure in children and may be beneficial in a subset of patients with mild to moderate PARDS. However, there needs to be close monitoring for worsening disease and NIV failure (7). In patients on NIV who do not show clinical improvement within the first six hours of treatment or have signs and symptoms of worsening disease including increased respiratory/heart rate, increased work of breathing, and worsening gas exchange (Spo2/Fio2 ratio), they suggest intubating, rather than continuing with NIV. For patients with possible PARDS or at risk for PARDS on conventional oxygen therapy or HFOT who are showing signs of worsening respiratory failure, a time-limited trial of NIV (CPAP or BiPAP) should be used if there are no clear indications for intubation.

Early recognition and treatment is key for patients at risk of PARDS and the PALLICC-2 guidelines suggest patients on a full-face interface of NIV (continuous positive airway pressure [CPAP] or bilevel positive airway pressure [BiPAP]) with CPAP greater than or equal to 5cm H2O or those invasively ventilated should be considered as having PARDS if they meet timing, oxygenation, aetiology/risk factor, and imaging criteria.

Oxygenation threshold to diagnose possible PARDS for children on nasal respiratory support include those on nasal continuous airway positive pressure/bilevel positive airway pressure requiring more than 40% FiO2 to maintain oxygen saturations 88-97% and those with high flow oxygen therapy at minimum flows:

- <1 year: 2L/min

- 1-5 years: 4L/min

- 5-10 years: 6L/min

- >10 years: 8L/min

Paediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (PARDS) is a complex and potentially life-threatening condition that requires prompt recognition and management. Early recognition and management of PARDS are critical in preventing further deterioration and reducing mortality rates. While significant advances have been made in the understanding and management of PARDS, much remains to be learned about this condition, including its pathophysiology and the most effective treatment strategies. Ongoing research efforts are needed to improve our understanding of PARDS and develop more effective treatment options.

Overall, PARDS is a complex and challenging condition that requires a multidisciplinary approach and specialised care. With timely recognition and appropriate management, however, the prognosis for many patients with PARDS can be favourable.

TABLE4. – Diagnosis of Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (Definition Statement 1.1; Definition Statement 1.7.1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Age (DS 1.1) | Exclude patients with perinatal lung disease | |||

Timing (DS 1.2) | Within 7 d of known clinical insult | |||

Origin of edema (DS 1.3) | Not fully explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload | |||

Chest imaging (DS 1.3) | New opacities (unilateral or bilateral) consistent with acute pulmonary parenchymal disease and which are not due primarily to atelectasis or pleural effusiona | |||

Oxygenation b (DS 1.4.1) | IMV: OI ≥ 4 or OSI ≥ 5 | |||

NIVc: Pao 2/Fio 2 ≤ 300 or Spo 2/Fio 2 ≤ 250 | ||||

Stratification of PARDS severity: Apply ≥ 4 hr after initial diagnosis of PARDS (DS 1.4.4) | ||||

IMV-PARDS: (DS 1.4.1) | Mild/moderate: OI < 16 or OSI < 12 (DS 1.4.5) | Severe: OI ≥ 16 or OSI ≥ 12 (DS 1.4.5) | ||

NIV-PARDSc (DS 1.4.2; DS 1.4.3) | Mild/moderate NIV-PARDS: Pao 2/Fio 2 > 100 or Spo 2/Fio 2 > 150 | Severe NIV-PARDS: Pao 2 /Fio 2 ≤ 100 or Spo 2 /Fio 2 ≤ 150 | ||

Special populations d | ||||

Cyanotic heart disease (DS 1.6.1; DS 1.6.2) | Above criteria, with acute deterioration in oxygenation not explained by cardiac disease | |||

Chronic lung disease (DS 1.6.3; DS 1.6.4) | Above criteria, with acute deterioration in oxygenation from baseline | |||

[1] Emeriaud G, López-Fernández YM, Iyer NP, Bembea MM, Agulnik A, Barbaro RP, Baudin F, Bhalla A, Brunow de Carvalho W, Carroll CL, Cheifetz IM, Chisti MJ, Cruces P, Curley MAQ, Dahmer MK, Dalton HJ, Erickson SJ, Essouri S, Fernández A, Flori HR, Grunwell JR, Jouvet P, Killien EY, Kneyber MCJ, Kudchadkar SR, Korang SK, Lee JH, Macrae DJ, Maddux A, Modesto I Alapont V, Morrow BM, Nadkarni VM, Napolitano N, Newth CJL, Pons-Odena M, Quasney MW, Rajapreyar P, Rambaud J, Randolph AG, Rimensberger P, Rowan CM, Sanchez-Pinto LN, Sapru A, Sauthier M, Shein SL, Smith LS, Steffen K, Takeuchi M, Thomas NJ, Tse SM, Valentine S, Ward S, Watson RS, Yehya N, Zimmerman JJ, Khemani RG; Second Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference (PALICC-2) Group on behalf of the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network. Executive Summary of the Second International Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (PALICC-2). Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2023 Feb 1;24(2):143-168. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000003147. Epub 2023 Jan 20. PMID: 36661420; PMCID: PMC9848214. Executive Summary of the Second International Guidelines for… : Pediatric Critical Care Medicine (lww.com)

[2] Jouvet P, Thomas NJ, Willson DF, et al. Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Consensus Recommendations from the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference. In: Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. ; 2015. doi:10.1097/PCC.0000000000000350. Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Consensus Rec… : Pediatric Critical Care Medicine (lww.com)

[3] Wong JJ-M, Jit M, Sultana R, et al. Mortality in Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine. 2019;34(7):563-571. doi:10.1177/0885066617705109 Mortality in Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis – Judith Ju-Ming Wong, Mark Jit, Rehena Sultana, Yee Hui Mok, Joo Guan Yeo, Jia Wen Janine Cynthia Koh, Tsee Foong Loh, Jan Hau Lee, 2019 (sagepub.com)

[4] Erickson S, Schibler A, Numa A, et al. Acute lung injury in pediatric intensive care in Australia and New Zealand: a prospective, multicenter, observational study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8(4):317–323 Acute lung injury in pediatric intensive care in Australia and New Zealand: a prospective, multicenter, observational study – PubMed (nih.gov)

[5] Dahlem P, van Aalderen WMC, Hamaker ME, Dijkgraaf MGW, Bos AP. Incidence and short-term outcome of acute lung injury in mechanically ventilated children. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(6):980–985. PubMed PMID: WOS:000187009900022. Incidence and short-term outcome of acute lung injury in mechanically ventilated children – PubMed (nih.gov)

[6] Wong JJ, Loh TF, Testoni D, Yeo JG, Mok YH, Lee JH. Epidemiology of pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome in singapore: risk factors and predictive respiratory indices for mortality. Front Pediatr. 2014;2:78. PubMed PMID: 25121078. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC4110624. Risk Stratification in Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Multicenter Observational Study – PubMed (nih.gov)

[7] Orloff KE, Turner DA, Rehder KJ. The Current State of Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol. 2019;32(2):35-44. doi:10.1089/ped.2019.0999

[8] The Current State of Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome – PubMed (nih.gov)

Meet The Author - Abby Lennon

Clinical Nurse Adviser, RN

Abby works alongside the Clinical Education Team to provide support and education to healthcare professionals using her knowledge and experience as a registered nurse working in respiratory wards and intensive care units over the last eight years.

Meet The Author - Abby Lennon

Clinical Nurse Adviser, RN